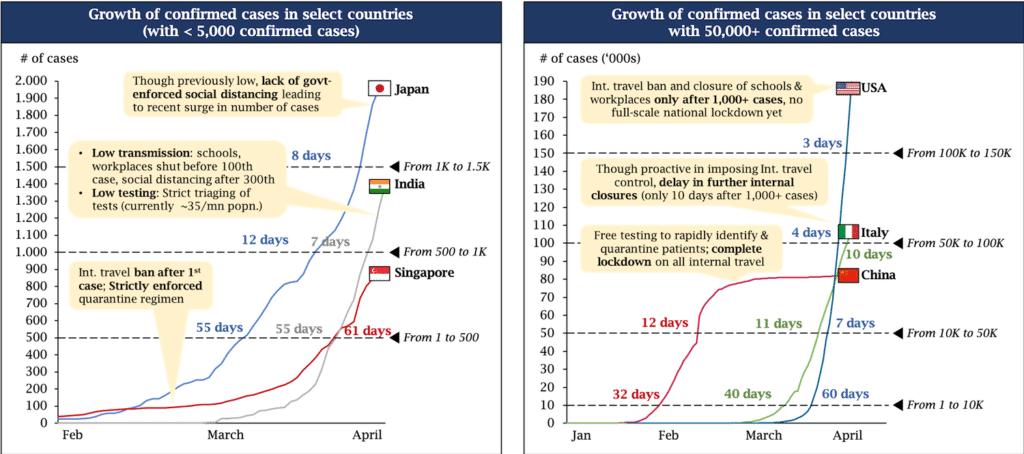

These are unprecedented times. The COVID-19 crisis has had a global impact, reaching a million cases and more than 50,000 deaths globally – numbers which are expected to rise in the weeks to come. Leaving alone the long-term implications, the situation is replete with uncertainty over how it will evolve, even over the next few weeks.

While China and a few East Asian countries seem to have shaken themselves out of the crisis, almost all other countries are at different stages in their disease trajectory. Despite claims of varied veracity of disease incidence linkages to seasonal and temperature dependence, protection from prior infection or vaccinations, and cultural patterns, most governments have slowly but steadily moved from a state of “if” to a state of “when” and “how big” the crisis is expected to be.

Fig. 1: Growth in confirmed COVID-19 cases has varied across countries based on the speed & strength of their response

Note: cases shown are as of 1st April 2020

Source: ECDC, KOIS analysis

1. We face a very complex problem; concerted action, not piecemeal solutions, is the need of the hour

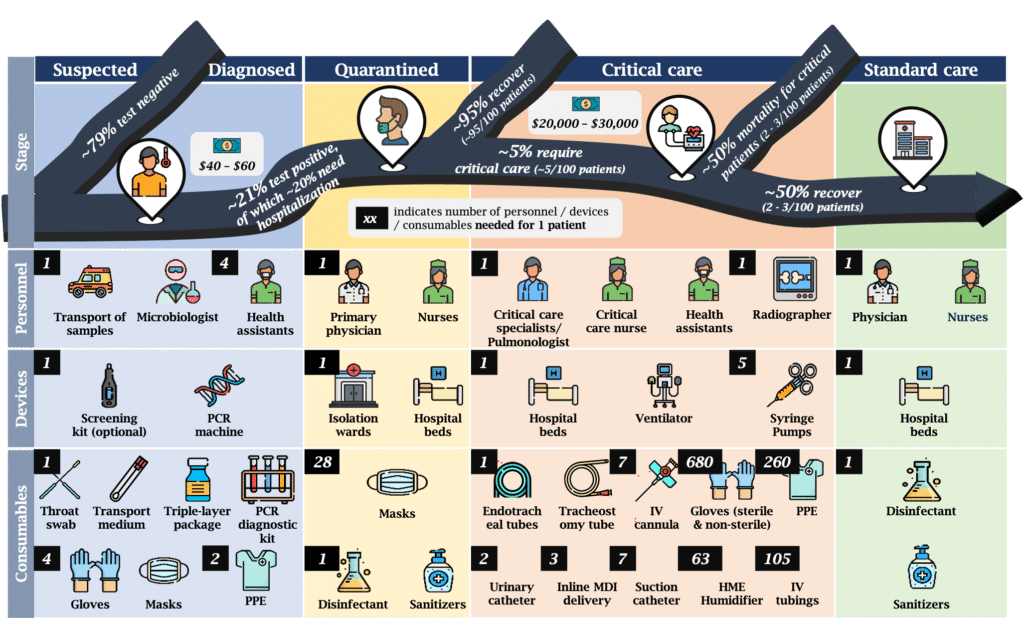

While most of the focus has been around ventilators and masks, experts predict that other critical supplies may run out even before these two. Modern diagnostic and critical care systems are complex entities, dependent on a myriad of labor and raw materials. For example, ventilators need trained critical care professionals to run them and require more than 20 different kinds of supplies to keep them running every day.

The severity of COVID-19 means that only highly trained intensivists, and not any specialist trained in the basics, can manage these cases. Moreover, the high infectivity means that many more supplies are needed to avoid cross-contamination within critical care units – now multiply that with the increased duration of ventilation with COVID-19 at approximately 21 days! Paired with the multi-fold increase in cases, this directly points to the need for immediately creating long-term projections of inventory needs across these numerous supplies, coordinating with suppliers, troubleshooting shortages, and circumventing conventional and ponderous procurement processes.

Fig. 2: Products & services required across a patient’s journey

Notes:

1. Costs shown may be borne by patients/govt, reflects actuals in India

2. All # are for care of 1 patient

3. ~21% rate for suspected – weighted avg. of USA, China & Italy case loads

Source: Expert interviews (special mention for Dr Pinak Shrikhande); Worldometers.info

Over the past few weeks, we have spoken to several actors including investees, funders, investor peers, medical experts and healthcare actors, to understand their response to the emerging situation. While a lot of action is happening on the ground, everyone appears to be working within their circumscribed ecosystems – understandably so. However, healthcare is rarely a localized and self-contained system in normal times; it is infinitely less so when facing a pandemic.

Supply-demand mismatches that normally even out over time get exacerbated as different actors vie for the same limited supplies from China and local markets. Hospitals seeing heavy caseloads are facing shortfalls, while those institutions that overstocked in anticipation of the pandemic may have surpluses stored in warehouses. While private players are still best suited to manage the international and local logistics, a centralized demand management system can effectively link up institutions (at the minimum, public sector institutions) with supply chains and match localised demand with supply. Hospitals can also better source non-traditional supplies from non-traditional providers through such mechanisms, such as gumboots from chemical factories and supply providers.

2. Governments should lead the way, but a response to this crisis will not succeed without the private sector

As countries brace themselves for the seemingly inevitable, actors across the spectrum have scrambled to mobilize resources. Governments have ramped up public health system capabilities and enacted financial security measures for citizens and businesses. However, governments also realize the magnitude of the challenge at stake and have looked to co-operate and co-opt the private sector.

The critical difference has been in ‘how’ governments have gone about this – from opening up financial assistance through development finance institutions, to providing national carriers on supply runs to China, to invoking emergency acts to force private manufacturing. Another key factor has also been an understanding of ‘what’ these different actors should do – case in point being the United States’ insistence on making their own test kits through the CDC, which eventually failed and resulted in a loss of crucial response time. On the other hand, India rightly depended on the private sector but has had hiccups in creating the right regulatory framework for testing and authorizing diagnostic kits.

Despite understandable roadblocks due to shutdowns and social distancing, private sector actors have done what they do best: convert huge challenges into huge opportunities. Healthcare actors are leading the charge in critical care, diagnostics, supply chain, and other allied areas. Screening and diagnostic tests with high sensitivity and specificity are already in the market. Non-healthcare actors have also repurposed their assembly chains to manufacture ventilators, hand sanitizers, personal protective equipment (PPE) kits and other essential supplies. Lenders are looking to re-allocate and deploy funds towards new customer segments that are being identified week on week. Venture capitalists and financial institutions are identifying normally unviable but suddenly rewarding investment opportunities to provide urgent and timely capital.

3. The private sector faces completely new challenges across the healthcare journey, and impact finance can help manage these strategically

Despite good intentions backed by tangible action, private sector actors are currently operating in unusual circumstances and face financing challenges, hitherto unseen. Impact actors, including donors, can de-bottleneck these activities through flexible financing mechanisms.

For example, supply chains and logistics have come under undue stress, especially with the origin point for many being China. Intermediaries need to commit to pre-agreed prices and delivery dates with healthcare providers but pay the price upfront and in full to manufacturers. However, they face back-end issues, ranging from (i) cargo stuck in Chinese manufacturing hubs that are suddenly locked down, (ii) disrupted land logistics that need to align perfectly with inter-country shipments, (iii) fluctuating prices for the same logistics due to rapidly moving demand patterns, and (iv) working capital risks with stuck payments.

This naturally leads to a state where intermediaries start prioritizing cash-and-carry buyers. While the most needy, public institutions would be heavily hit in such a scenario due to their more stringent procurement processes. Donors can help by a) providing highly concessional working capital loans to intermediaries, or b) providing concessional pre-financing to lock in output from scarce manufacturing capacity, or c) guaranteeing a price to intermediaries and supplementing shortfalls between pre-agreed prices to eventual costs.

This reduces the cost of capital for intermediaries, thus enabling them to align shareholder value to public health value (and serve public health institutions when they would otherwise not).

In the medium-term, COVID-19 may see the fastest time-to-market vaccine ever, as envisaged by Bill Gates. However, that’s just part of the puzzle: volume guarantees assuring a given quantity of procurement may be needed to ensure that manufacturing capacity is built ahead and in time to dovetail with the transition from labs to factories.

4. This is not just a healthcare crisis; impact finance is needed to address the looming livelihoods challenge

Microlenders, traditional and mission-focused, are looking to provide concessional financing to a workforce that is temporarily out of employment due to the crisis. However, this demographic segment lies outside their comfort zone. Many do not possess bank accounts, let alone a long enough banking history. And this is not a livelihoods loan; it’s the exact inverse – its purpose is to help you stay home. At the same time, corporates and groups of individuals have looked to donate or fundraise for different interventions to support this segment. As well-intentioned and much needed as these interventions are, they will only reach limited numbers of the needy. Potential exists for blending these two funds – for-profit and philanthropic – together to generate a multiplier of sorts for the possible impact.

These are atypical financing needs and may therefore demand atypical and innovative financing structures. We see two possible structures across two different demographics. Firstly, the gig/semi-formal workers (for example, Uber drivers) possess a relatively higher ability to pay and a reasonable banking history. However, lenders would stay away given the lack of clarity on the horizon of re-employment, and the level and timing of rebound of the job market. If foundations and fundraisers can provide a guaranteed repayment period, that would enable them to negotiate highly concessional lending by lenders who are eager to deploy their funds in these tumultuous times. Secondly, low income workers, such as construction labor in India, possess a lower ability to pay and no banking history. Fortunately, governments have proposed financial support to this population through direct benefit transfers. Unfortunately, large numbers of this segment do not have the bank accounts or the right scheme enrolments to avail this monetary support. Philanthropic money from well-intentioned donors can be utilized to create bank accounts and enrolments to unlock much larger government disbursements and provide more sustainable support to these segments ($10 of your money unlocks $100).

In conclusion, we foresee that the ongoing scenario will significantly change how healthcare, financial, and logistical ecosystems function and therefore how impact actors operate. Telemedicine, the healthcare sector’s perpetual bridesmaid, may finally have arrived – although many customers may drop off when the pandemic ends, many users will continue to use the telemedicine services. Diagnostics will shift towards more point-of-care systems, wherever possible. Lenders may discover previously untapped demographics.

We aim to cover our learnings on the long-term role of impact finance in light of emerging trends in a follow-up article.

About the authors

Dr Prabu Thiruppathy is a Principal at KOIS in the Mumbai office.

Dr Serena Guarnaschelli is a Partner at KOIS in the London office.