LGT Venture Philanthropy (LGT VP) deploys philanthropic growth capital to organisations with effective, innovative, and scalable solutions to social and environmental challenges. Late last year, LGT VP funded KOIS to prepare: “Primary Care: A Landscape Report”. The report is centered on India’s primary healthcare ecosystem. The study helped refine LGT VP’s India healthcare strategy, prioritising support towards strategic areas within primary care in line with LGT VP’s investment criteria. Here, we share the study’s key findings to stimulate a broader discussion on the topic. The findings strongly resonate with the team’s on the ground learnings over the years.

India has an extensive public primary healthcare network, composed of ~23,000 Primary Health Centres (PHCs) and ~146,000 Subcentres that collectively cater to millions of patients’ health needs annually. This network, however, continues to be plagued by three critical issues:

- Lack of access: Patients often need to spend a lot of time and resources to access/reach a government PHC¹. For example, there is a ~22% shortfall in government PHCs and an ~18% shortfall in Subcentres in rural India.

- Lack of affordability: Due to perceived gaps in quality2, patients are twice as likely to seek out private clinics as compared to government PHCs. Even though it is estimated that expenditure for visiting a private clinic is ~2x (USD 8/visit) of the amount incurred while visiting a government PHC (USD 4/visit3).

- Low quality: Government healthcare facilities are often ill-equipped to provide quality healthcare to patients. They face challenges such as shortage of medical personnel (e.g., ~25% of PHCs do not have doctors), drug stock-outs, and critical gaps in infrastructure (e.g., ~17% of Subcentres do not have regular water supply).

I. Private operators can play an essential role in complementing the public primary care network

The government aims to address these challenges through its ambitious Ayushman Bharat program. Launched in 2018, the program aims to: (1) establish 150,000 Health and Wellness Centres (HWCs) providing comprehensive primary care; and (2) provide an INR 500,000 (USD ~6,800) health insurance coverage to over 100 million low-income families for secondary and tertiary care. However, the establishment / upgradation of the HWCs will take time and the health insurance provided by the government does not cover primary care. The emergence of universal access to quality, affordable primary care may therefore take longer.

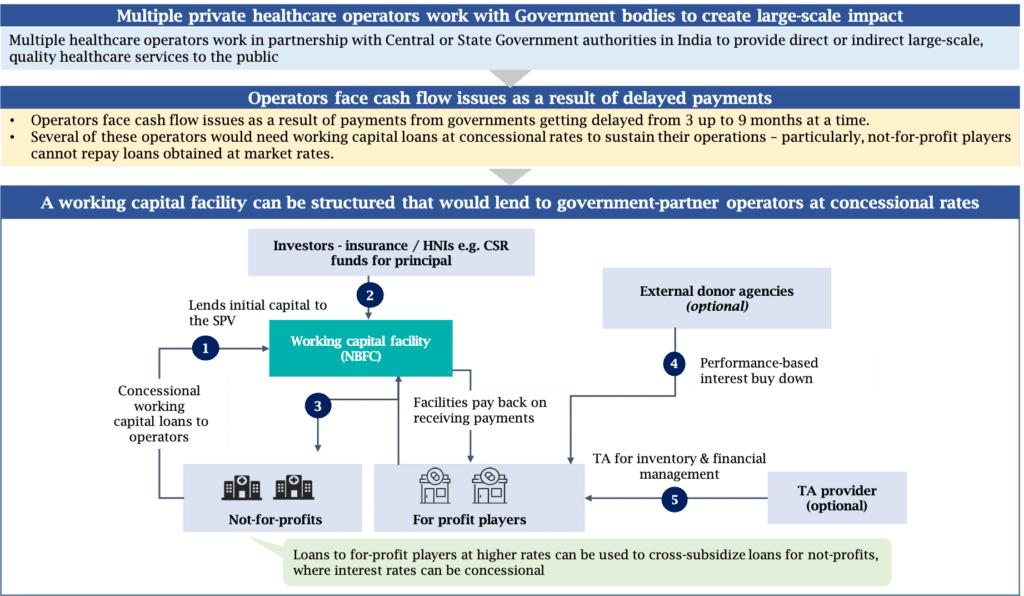

In the meantime, private healthcare operators can play an instrumental role in complementing the public health system’s offerings. Operators, with diverse business models, may attempt to do one or more of the following:

- Increase access to care. For instance, through deploying mobile medical units in underserved areas;

- Improve affordability. For example, by providing healthcare loans;

- And deliver better quality. For instance, by running healthcare clinics offering comprehensive, high-quality primary health services.

II. Funders can provide crucial support to financially constrained private operators

Several healthcare operators provide good quality services at concessional rates to underserved populations. However, the majority of these operators frequently face financial bottlenecks. This is a result of their inability to generate adequate revenues to cover their costs.

We consider the example of a private brick-and-mortar health clinic in rural Bihar that caters to nearby villages. It cannot charge high prices for its services, given the patients’ low ability to pay, as well as the ever-present alternative of free services at government PHCs. At the same time, this clinic has a high operating expenditure (~40% higher unit costs than government PHCs). This results in the clinic finding it tough to break even and maintain the same service levels. Many private operators across the country face this problem.

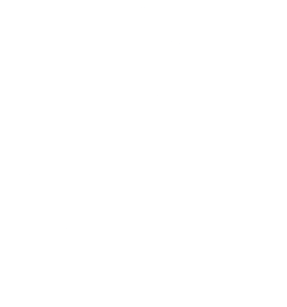

Other operators with different models may not charge patients for their services. For instance, operators focused on generating awareness of better health practices amongst the community. Some of these collaborate with the government to partially cover their costs. They then meet the remainder of their funding needs through donor grants.

Funders, therefore, have a crucial role to play in uplifting India’s primary healthcare ecosystem by supporting these financially constrained operators. They can extend their capital in a variety of contexts. Providing (1) start-up capital to help operators establish proof of concept; (2) funding to help operators sustain current operations; and (3) scale-up capital to help operators expand existing, proven models. Funders can also provide complementary non-financial support in the form of access to networks, talent, experts, and consultants to strengthen the capacity of these operators.

III. Funders can leverage outcome-linked, innovative finance instruments to maximize the impact of their capital

Even today, most grant funding focus on inputs and are programmatic in nature. These traditional funding pathways limit the scale of impact possible since funding is allocated is to a program for a specified duration. Moreover, funders have no assurance that the intended outcomes will be met since funding is tied to inputs and not the achievement of outcomes. Outcome-linked instruments and more broadly, innovative finance instruments, can help address these challenges.

By linking payments to achievement of select, predetermined outcomes by operators, funders can bring more accountability and transparency into the sector. This helps provide them with visibility on how their funding is getting utilised as well as the consequent impact being generated.

Innovative finance refers to a range of approaches to mobilize resources and improve capital efficiency and effectiveness. These approaches include an array of instruments across a broad spectrum:

- traditional development assistance (such as grants or co-pay)

- conditional funding (such as impact bonds or value-based pricing)

- catalytic funding (such as financial or volume guarantees)

- outright commercial investing (such as concessional loans or micro-finance).

These instruments can be contextualized to effectively help achieve outcomes in a more efficient and targeted manner. (Exhibit 1 and 2)

Operators can benefit from the use of innovative instruments as well. By institutionalising M&E frameworks, operators can move towards measuring and streamlining the impact of their interventions. Doing so helps showcase their readiness to collaborate with outcomes-driven funders. It also significantly increases the likelihood of operators securing the funding for their work. At a macro level, these mechanisms can be used to create an evidence base for non-traditional solutions, thereby effectively increasing the scope of interventions that funders can support.

The ongoing crisis has forced both funders and operators to pause and reflect. Not only to critically reassess their existing approaches but also to focus on building resilient and sustainable models. The need of the hour is to explore the use of different models, including innovative financing instruments to drive forward the agenda for digitally empowered, scalable models solving for improved access to affordable, high-quality primary healthcare on a sustained basis to underserved communities in India.

KOIS is currently exploring partnering with other stakeholders in the primary care ecosystem to convert these opportunities to reality. We would like to use this platform as a call to action for funders that firmly believe in directing resources to catalyze the growth of primary care in India.

- The number of PHCs and Subcentres required, and therefore the current shortfall in their numbers, is calculated on the basis of the provisional rural population as per the national Census.

- Niti Aayog report, Lancet report

- Despite free treatment at Indian public health facilities, the cost of drugs and transport to facilities leads to out-of-pocket expenditure by the patients.

About the authors

Gayatri Suri is a Senior Investment Professional at LGT VP

Abhishek Kapoor is a Senior Analyst at KOIS Mumbai